Software Rot

The first issue is about engineering mature software products.

It is a painful reality that all software decays. Some call it ‘code rot’ or ‘software erosion’, whatever the name, it is inevitable that software will slowly become difficult to maintain or even unusable.

First, the hardware that the software must run on is constantly evolving, so although you may have a working software and hardware combination today, one day the hardware will fail and you will have to replace it. At that moment you will discover that the old software does not run on the new hardware, or some key feature fails to work (this is particularly the case where the software meets the hardware in graphics cards and other peripherals).

The user requirements don’t stand still either. They will face new file formats and standards. User expectations, particularly in the realm of the user interface, ease of use and responsiveness will change over time too.

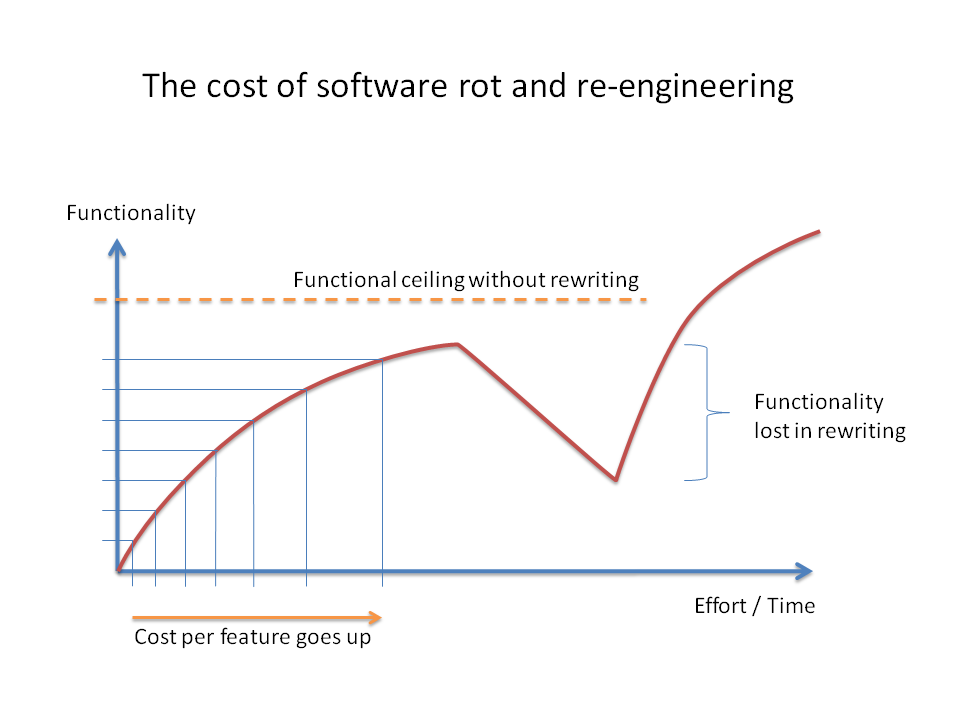

At the same time a mature software application becomes harder and harder to add features to. Think of it as a complex mechanism. Every time you add new functionality, that complexity increases, and that gives you more things to consider when adding the next new feature. The chances of breaking existing functionality when you add new features goes up dramatically, and consequently testing becomes harder and more time consuming.

Ultimately this pile of complexity becomes so bad that the engineers insist on starting again and ‘rewriting from scratch’. To achieve this takes a whole heap of time and you inevitably end up with fewer features (as the pressure to release the product eventually overtakes the engineering attempts to recreate legacy features). The inevitable reaction from the market is “Why did we have to wait so long for less features?”

Diminishing Returns

The second issue is about selling a successful mature software product.

If the product has gained significant market share, there will be a diminishing pool of new customers. New functionality is added to swing those customers. Remember that each new feature is more and more expensive because of the ‘code rot’, and each new feature attracts fewer and fewer new customers. So the cost of acquiring each new customer is going up exponentially.

At the same time the company goes looking for ways to expand its market. For any company that is in a tiered market (‘professional’ to ‘consumer’, ‘specialist’ to ‘generalist’, etc) it will inevitably seek to go ‘down market’.

The Final Premiere Pro X Cut Story

What is interesting about the latest round of the FCP X story is that it is linked to its biggest competitor, Adobe Premiere, by (at least) two people. I’ve patched together a combined history.

Star video software engineer Randy Ubillos starts writing Premiere at Adobe and they release the first version in 1991. Randy stays for 3 or 4 releases and then jumps ship to Macromedia to start again with Key Grip, shown privately at NAB 1998. At around the same time a product manager called Richard Townhill starts work at Pinnacle (who also do editing systems).

After some horribly convoluted licensing issues between Microsoft, Truevision and Apple (don’t bother to ask), Apple buys Key Grip, Randy follows, and they show it publically for the first time as Final Cut at NAB in 1999. In 2001 Richard moves to Adobe and oversees the re-writing of Premiere, which after around 12 years must have had some ‘rot’, so they renamed it Premiere Pro. He hung around for a year or so before heading off to … Apple, in 2004.

In 2007 Randy tires of FCP and starts work on iMovie.

After Version 7 of FCP in 2009, it looks like they started work on building a completely new FCP based upon the iMovie code base. A ‘rot’ based decision? This is released in 2011, 12 years after the first release. Richard does the presentations at NAB where he announces that although Final Cut has 1.5m ‘users’, they are aiming for 3m with FCP X. That was the hint that the professional video users should have picked up on.

Confused? Here is a simplified timeline for you:

I get a feeling of déjà vu, Randy and Richard must feel like they are stuck in ‘Groundhog Day’.

Who is FCP X Aimed at?

So when FCP X finally appeared, what were the features that were lost in the re-write? Well, certainly not the user interface which looks gorgeously slick and neat. Ease of use is right up there too, with lots of things to make it easy for people to get the footage looking nice without having to try too hard (by the way, professional editors don’t make the footage look nice, they get colourists to do that for them).

Capturing footage off tape or recording it back to tape? That’s gone. Loading old FCP v7 projects? No need for that. Handling complex multi-camera productions? Nope.

I’ve written before about the small size of the film and television post-production industry, but Ron Brinkman, who I like and respect a great deal, has related that to Apple’s decision in a recent post: http://digitalcomposting.wordpress.com/2011/06/28/x-vs-pro/. He guesses that there might be 10,000 high-end professional editors in the world. I think there might be 200,000 professional editors in the world (not necessarily ‘high-end’). What the heck does it matter? Looking at Apple’s target market of 3m users, Ron’s figure represents 0.3% and mine 6%. Either way, I’m sure it is below the radar as far as Apple Product Management are concerned.

Are you getting the message yet?

A Final Chasm

I think Apple faced a classic problem (The Chasm to those in the know) in developing the market for FCP. They had saturated the professional market and had to look to the semi-professional and pro-sumer (professional-consumer) markets to grow beyond it. Apple are a consumer products company, for whom professional users concerns are a bit of a pain in the ass with a whole bunch of complex needs to solve everyday workflow problems. As Ron Brinkman puts it: “Apple isn’t big on the quotidian.”

So often, as you move from your early adopters to your majority market, you have to change your focus and concerns dramatically. Your majority users will have very different needs. In this market they are: ease of use, quick to learn, digital media camcorder formats, make it look nice, low skill, etc. This compares dramatically with the professional market which is concerned with workflow, depth of features, complex productions, delivering video tapes, and speed of use. They’ll learn how to use the most complex feature if it saves them time. The fact that they managed to keep both professional and hobbyist users happy with FCP v7 is remarkable and a testament to their product design.

So to make the product what your majority market needs, you sometimes have to do the opposite of what your early adopters wanted. If you piss off a few thousand gnarly old editors whilst chasing your $1bn market, well that’s just collateral damage like having to break the odd egg to make an omelette.

How should the professional users act in such a market? Ron has some advice:

“So if you’re really a professional you shouldn’t want to be reliant on software from a company like Apple. Because your heart will be broken. Because they’re not reliant on you. Use Apple’s tools to take you as far as they can – they’re an incredible bargain in terms of price-performance. But once you’re ready to move up to the next level, find yourself a software provider whose life-blood flows only as long as they keep their professional customers happy. It only makes sense.”

Think it through, guys. If you want to get the attention of manufacturers, you’ll need to offer them a respectable market. If we asked you 200,000 editors to support a 1$bn market, you’d need to be paying $5,000 for your editing software. If we asked just the 10,000 high-end editors … oh forget it.

After programming for 20+ years I agree with you about software rot. That is a factor that folks just do not understand. That is one of the advantages of open source. Open source does for software writing that distributed computing does for software execution. Asking one company to continue to support a legacy program for a small market is not consistent with the needs of a stockholder driven organization.

Thanks for the comment Christopher. I can see that open source can help with the rot, but attempts to break into the film & TV market have not worked yet. It will be interesting to see if Lightworks bucks the trend.

I suppose open source NLEs are destined to fail because of the same reason: not enough prospective users to interest programmers. So that brings us back to the software-for-profit model, and that means FCPX!

Yep, someone has to pay for something at some point…

Despite common GUI elements, FCPX is not based on iMovie. iMovie is Quicktime based whereas FCPX is AV Foundation based.

If there’s a close lineage it would be iMovie for iPhone/iPad which are also AV Foundation based.

While high end pros don’t count for much of the sales, they do count for marketing.

Many aspiring editors use a program because they believe they will one day get paying work, whether working in broadcast, post production facilities or freelance. If pros don’t use the program, it means those with pro aspirations will also look to something else. Add the education market to all this as well since such institutions want be to learn skills that can result in careers.

Thanks for the comment Craig.

Hmm, so how do you explain the fact that FCPX does not load FCP7 projects, but does load iMovie ones? You may well be right, but it looks pretty obvious to an outsider (and I’m definitely an outsider as far as Apple is concerned).

Yes, there is marketing advantage to having high-end users use your app. The high-end users have been using that excuse to squeeze big discounts out of professional app manufacturers for years… My point is, that when it comes to one or the other, the maths says “stuff the pros, build for the consumers”.

There is no fault the Apple’s business logic. But the application of it inflicted unnecessary damage to everyone. Certainly the world can use another approach to video editing, but the highhanded manner that Apple rolled it out cast a shadow on the product itself, and needlessly insulted a large and loyal group of customers. And I don’t mean just high end editors. Nearly every educational institution I know of that teaches video, uses FCP. That will change soon, as more educators and administrators jump ship to Adobe. Some may want to hold on to FCPX, but the product has become synonymous with “unprofessional”.

I get it that Apple doesn’t care about professionals anymore, just consumers. It may be a more rewarding market, but it’s also a more volatile market. Apple’s profits are impressive, but also rather recent. But this insular, rather arrogant corporation also has clear leadership issues. Let’s hope they work it out, if only for their stockholders.

Thanks for the comment Patrick.

Yes, you are right, FCP7 and FCP Xpress had a huge user base, and they will be disappointed by Apple’s actions. I certainly think that Apple have messed up on the roll out of FCP-X here. They should have continued to support FCP7, including license transfer, maybe the odd patch, and not have FCP-X remote 7 on install (which I believe it does), so that folks could continue to use it until FCP-X catches up on the missing features (if it ever does).

Missed opportunity to keep those loyal customers on side.

Great minds…

Thanks for the comment Adrian, and a good post by you too. I agree with your conclusions.

I do agree that Apple is trying to goto a more broad audience but don’t think they meant to alienate pros at the same time.

Over history of graphical applications whenever companies have rebuilt an extablished package of software from scratch they typically leave large gaping holes with missing features which we’re standard in the previous release. Autodesk made this huge mistake with Autocad 13 back in the late 90’s. The new release was missing major functionality. Sales went flat till they started including Autocad 12 with 13. It wasn’t till Autocad 13 v4 that they actually filled in the large gaps. It took till after v14 before people started trusting the new releases again. Maya 1.0 and Softimage 1.0 has similar issues and had to include Power Animator/Modeler and Softimage 3d respectively. It wasn’t till 2-3 years later before the previous mentioned included all the missing features. There countless other examples of this occuring in the industry.

Even Apple itself has done this with Quicktime X and iMovie 8. Quicktiem 7 is included with Snow Leopard because X is feature incomplete and has less features. Also iMovie 8 included iMovie 7 because it was missing lots of basic items. It wasn’t till iMovie 9 before it was flushed out.

Thanks Deke.

Yes, unless you are prepared to leave a very long time between releases (and no management is likely to sanction that), then a rewritten product is going to be missing shed loads of features. It’s inevitable.

Just came across Seth Godin’s idea of a creation having a “half life” – neat term for software decay! http://sethgodin.typepad.com/seths_blog/2011/07/half-life.html

Read the struggles and tribulations of experienced editors as they wrestle with the paradigm shift: http://philipbloom.net/2012/02/07/fcpxeditors/