I first considered this question forty years ago.

In the early 80s I had become fascinated with the use of computers in art and design. Studying architecture, I was frustrated with the process of drawing my designs and intrigued by the promise of computer aided design.

I have always had an attraction to the counter-intuitive, not to say the improbable. In the early 1980s the idea of using a computer in serious art and design seemed unlikely, however commonplace it now appears.

After graduating I went to the Royal College of Art and to research how computers could be used in architectural design. My thesis from 1982 is entitled “The Architect’s Apprentice: The Application of Expert System Techniques to the Early Stages of the Architectural Design Process”. An expert system, an early commercial success of artificial intelligence research, emulates the decision making of a human expert, such as a doctor.

My thesis pleaded with the architectural profession to wake up and realise that computers would soon be a vital tool in their daily lives. It suggested that the best way to use such tools was in support of the creative process, rather than replacing it.

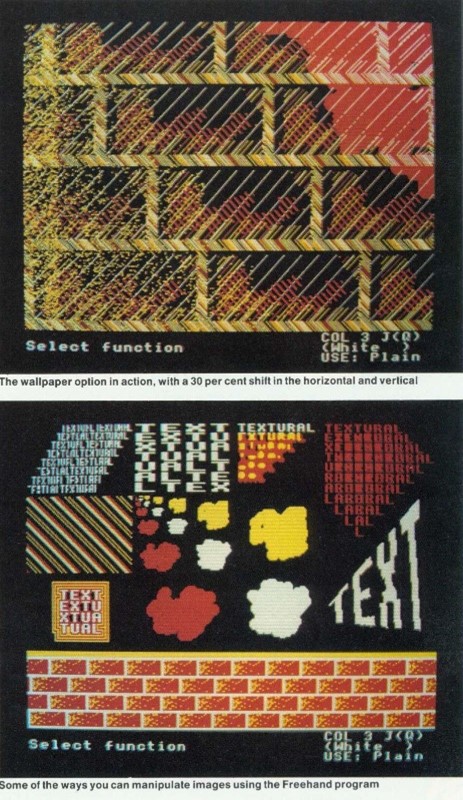

I went on to teach about computers in art colleges, published a paint system in Acorn User in 1985, joined ITN to work on animated graphics in 1986, then software companies helping artists produce breath-taking special effects.

Sitting beside artists in the 80s and 90s as they used our software was a thrilling experience. They were creating images and animations that would not have been possible without these tools (and a lot of very expensive high end computer hardware).

I’ve returned to thinking about AI in creative industries now, in 2023, and am as fascinated as ever. I will be writing a series of posts about my thinking and my explorations.

To kick this off I completed a course with Oxford University over the summer in Developing Artificial Intelligence Applications. It was amazing and I’ll share some of what I learned in the next post.

Later posts will cover topics such as:

- What does creativity mean in relation to AIs?

- Some good, and bad, ways to use AIs in the creative industries.

- Is Artificial Intelligence magic?

For now, back to the question and that 1982 master’s thesis. First question is why is applying artificial intelligence to an activity which involves creativity, different from applying it to one that doesn’t. Well, a creative task (a design problem in my thesis) is what some have called a “wicked problem[1]”, one where there are no right or wrong answers, only better, more satisfying or even good enough ones. Furthermore, in attempting to come to a solution to such a problem the artist or designer must go through a cyclical process of hypothesise, invent, trial and test, then repeat. This cyclical process is one which potentially has no end and may never deliver a satisfactory solution.

I think many activities involve creativity, whether solving a technical problem or coming up with what to cook tonight. What makes the creative activities like design different is the degree to which they are “wicked problems”.

What I proposed in 1982 was that while a designer wrestled with, perhaps “delight” through this wicked problem, the computer aid could be testing it and delivering feedback on “firmness” or “commodity” (to use Vitruvius’s 2,000-year-old definition of a good building design).

I believe the right way to use any tool is in the support of creative activity. Yes, we can use these tools to replace some elements of the work involved in any activity, whether making it easier to tighten a nut, generating perfectly seamless textures, or driving a car. Ultimately, we must decide what it is we want to do, then use whatever tools are available to achieve that aim.

I know that we have AI writing books, creating complete images, synthesising voices, etc. The value of these things is a philosophical problem but hey, let’s not try to run before we can walk.

Next up, what are AIs and how do you build them.

[1] Rittel & Webber, Dilemmas in a Geneal Theory of Planning, Policy Science 4, 1973